Zid: 50M Orders Later

We have come a long way in our technology and product since our last post back in 2019. Our product suite has grown from only an online shop to a multi-channel, multi-modal commerce platform. We now have a POS, a marketplace (Mazeed), integrations with prominent marketplaces (e.g., Amazon, Trendyol, Jahez), and an API that allows developers to extend our platform. All of which required us to make multiple significant shifts in our infrastructure and architecture.

In this post, we will share a few pivotal projects we worked on that helped us get to where we are, and we think they will help us move forward. We will present the projects in chronological order of their kickoff, yet their efforts might have overlapped or were dependent on each other – for example, the new theme editor was dependent on the new dashboard being completed to be able to build it on the new system.

New Checkout System

The checkout system was probably the most significant source of fear whenever someone discussed potential rewrites. The legacy (then-current) checkout system was part of the PHP monolith, carrying over the open cart mess with it. The cart concept was spread across 12 tables, at least 9 of which are required to load the cart every time it is needed – plus the related non-cart-specific tables (i.e., products, coupons, etc.), so you would end up with queries to 15 tables just to load the cart. And most importantly, there was no clear structure for how the cart is evaluated. It was very difficult to track what was changing the cart’s values. Calculations for product prices, tax amounts, discounts and coupons, and shipping fees were structurally intertwined. Making the system so fragile that we were too afraid to dare to think about touching it. Only three people in the company were competent enough to work on it, and only one person was confident doing so.

Since our last rewrite, Python's popularity at Zid has risen. More engineers on the team are now comfortable contributing to our Python services, which made, mostly, a straightforward discussion that we should use Python for the new checkout[1]. The more involved discussion was on the choice of the datastore and framework. We knew that we did not need a relational database. Actually, a relational database would have defeated the purpose of this rewrite. That is because a cart system’s access patterns are predominantly primary-key accesses. The system would generally read exactly one key, or update exactly one, so no need for the strict transactional ACID guarantees provided by the rational database[2]. We were between choosing DynamoDB and MongoDB. We went with MongoDB at the end purely to avoid vendor lock-in.

The rewrite took a whole year. Implementing the base cart logic was not so complicated, but integrating that with the rest of Zid was a tremendous amount of effort. For example, we needed to integrate with our shipping module. The shipping module not only facilitates generating waybills but also determines which shipping methods should appear to the end customer during checkout. Shipping methods in Zid can be customized per city, allowing the merchant to set availability and pricing for each city. To ensure compatibility with all previous business logic, we were running our PHP cart test suite (~2000 tests) on our new system.

More importantly, we needed to ensure that the migration is done store-by-store, is reversible, and is unnoticeable to merchants and customers. Meaning, if the customer was in the middle of a session, that session should not be disrupted. So, we spent a good amount of time implementing mechanisms to import and backport carts based on which system was activated and which cart was used. To do this, we also had to preserve client compatibility with the APIs, so we used the same APIs and implemented pass-through calls in the old backend controllers.

Rollout was done store by store; that was a deliberate design decision to minimize the blast radius of any issue. We added stores to the pilot in batches based on their feature sets and their daily orders. We started with stores that had fewer orders at first to see how the system behaves under increased traffic, compared to our tests.

Today, this system has been in production for over two years. It has been the basis of many of the checkout features that we released since then. Features like guest checkout, single-page checkout, on-product-page checkout, automatic discounts, discount conditions, open pricing, and more to come. The new codebase has made altering the checkout flow a streamlined and predictable process compared to where we were.

New Merchant Dashboard (Hermes)

The Merchant Dashboard has always been a very awkward topic of discussion among the engineering team. It was originally built as a PHP/Laravel app. The role of Laravel was purely to do server-side rendering. It was communicating with the backend through the API. There have been five attempts to refactor this system. First, we tried SlimJS components to make the app more interactive. Then, we decided to move to VueJS for the same purpose. Later, started a full refactoring project to migrate the whole app to an SPA. Afterwards, did a refactoring of the refactoring to introduce a homegrown design system library.

All the aforementioned projects failed, but we still did ship their results to production. Meaning the codebase was bloated with all of these attempts and refactorings. There were a ton of ways to do the same thing, and a ton of boilerplate was needed to accomplish any task. Also, the merchant dashboard became a BFF (backend for frontend) app where the backend is a PHP/Laravel system, and the frontend is, mostly, a VueJS app. The issue was that the relationship between the BFF, the frontend, and the “backend backend” was not quite well defined. Some logic was done in the BFF, and other things were in the backend – it depended on who had the time to do it. Over time, that made frontend development a slow, tedious, and error-prone process. Any change was guaranteed to have defects.

The decision in late 2024 was that this time we will not refactor anymore – it is a lost cause. We settled on a full rewrite. We will start from scratch. An SPA app from the start, with a very thin BFF layer to manage the token (a constraint of our auth system). We used React with Remix, and with Caddy as the BFF[3].

Given that we are rewriting the dashboard, we took the opportunity to revamp its design and UX. We assembled a workforce across design, product, and engineering to overhaul the dashboard’s UI from the ground up. We knew we would have to redo the UI, so we decided to join forces. This sounds great; however, the project no longer had a defined scope. Designers can be as creative as they want, and we do not have a well-defined set of boundaries for what is in the project and what is not, which led to the project extending for much longer than originally anticipated.

We kept working on feature parity between the old and new dashboards internally until we reached a comparable state. At that point, we decided to release a pilot, have some merchants test it, and gather feedback while we continue implementing missing features and improving the dashboard's stability and UX.

New Storefront System (Vitrin)

The storefront (aka catalog) is the component that end customers (i.e., buyers) interact with to shop at any Zid store. It is our merchants’, and consequently our, bread and butter. Any outage in this component directly equals money lost. Earlier, I mentioned that Checkout was the scariest project to think about; the storefront project was the most overwhelming. The scope of what falls under the storefront and what could be affected by the project is too intimidating to even sketch a plan. We were avoiding it for so long.

The core issue with the old catalog system is that it was originally built as a prototype with a single theme and only customized through a few switches that changed some colors and a few icons. Later, we added a few Zid-built themes that merchants can choose from. The year after, we opened the system for external customization from theme developers. Every iteration was more or less planned to be just a PoC that we would go back and fix later – that never happened.

Compounding workarounds and hacks got the system to an unmaintainable state. The smallest of new features required significant effort to implement, and, most importantly, it performed so poorly that our merchants were complaining about the speed of their store’s FCP[4]. To improve this, we introduced improvements to our infrastructure outside of the catalog, as we did with Zaddy. Yet, these were all bandages, not cures. We were too concerned about touching the system to risk cascading failures when changing any part.

We decided to completely give up on the old system and start from an empty text file. We opened the text editor and started experimenting with new approaches for every piece of the stack. Theme storage, static file handling, page context gathering, caching architecture, and page rendering were all rethought with all the context and experience we gained over the years. We put a few guiding principles in place for this project to be able to measure the quality of our decisions.

First, we wanted to be able to serve as much as possible with only cache. Meaning that almost every request should be cacheable. Non-cachable requests are the exception, not the norm. We even store themes in an in-memory database. We used a repository pattern where every repository is cachable by default – abstracting the caching nuances from engineers; they only need to specify the TTLs.

The second principle was that we need to achieve a better performance-to-cost ratio. The old system was only stable because we were throwing money at the problem. We had huge individual pods[5] that we ran a few hundreds of, making scaling up a time-consuming process of EKS needed to provision new nodes for any reason. That is why we wanted an architecture that would help us deploy many small instances while still achieving relatively good performance per instance. We settled on FastAPI because 1- it is in Python, and 2- it is asynchronous. This system spends the majority of its time doing I/O. Calling the backend or calling cache to get something[6]. Also, with Python 3.14 now supporting Free-threaded mode, we expect this metric to improve.

Something that influenced our choice to go with Python was Jinja2. We were testing multiple JavaScript templating engines, but none ticked all the boxes[7]. Jinja was the most mature and feature-rich of the bunch – though we had to invest in async support[8].

With those two principles, we set our test to render the homepages of the stores. We chose a real store and tried to mimic a simplified version of its settings and customizations on the new system. We did that to ensure that our tests reflect real use cases of known problematic configurations in production. If we can improve these cases, the easier cases should improve as well [9].

Once that foundation was laid, we moved to the implementation phase. It is just going through every page, endpoint, and templating feature, and writing them in the new system following the new principles. Some things were reconsidered in terms of whether they should continue to be part of the system or whether we should no longer support them. It was a good opportunity for us to reevaluate the templating system's feature set, given that theme developers will need to perform a migration step anyway.

The rollout phase was, again, gradual. We chose one of our themes and migrated it to Vitrin. We chose a small batch of our merchants that use that theme and enabled the flag on them (more on how we route requests in the next section). We added more merchants as we go, and covered edge cases as they arise. Once we got to a stable state, we moved all merchants running this theme – 10% of Zid merchants.

Now, another challenging part of this project is partner migration. Not all themes are built by Zid. In fact, only three themes are built by Zid. The rest of ~200 themes on the marketplace are built by partners. We needed to ensure we had comprehensive, detailed documentation and a migration guide. We documented the multiple experiments we took ourselves to migrate our theme. Then wrote a reference and a best-practices guide. The challenge is that not all are collaborative or willing to collaborate.

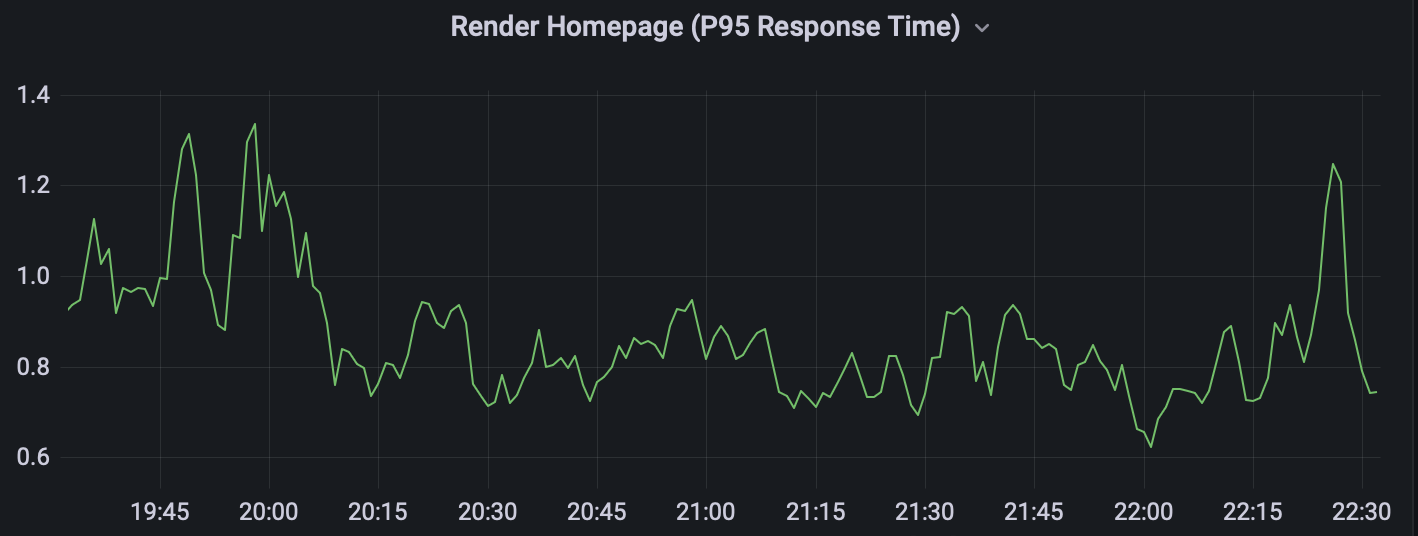

It is worth mentioning how much this new system has improved the experience of our merchants and their customers. We tracked two core metrics to measure improvement: response time and conversion rate. The theory is that faster response times lead to better conversion rates. When we say response time, we are specifically talking about how long it takes our servers to render a page. We are not necessarily talking about FCP (first contentful paint), given that it is highly dependent on the theme developer and how they implement their theme[10]. We had stores that took over 40 seconds in the good times and never loaded under load. We now have these same stores load in under 1 second! We now have monitoring across the entire platform to ensure we target a P95 of under 1.5 seconds.

For the second metric, conversion rate, we refer to the percentage of visitors who buy out of the total number of store visitors. We have seen conversion rates increase by up to 50% in some cases, with an average of 20%.

Zaddy (doubling down on Caddy)

As discussed in a previous post, we rely on Caddy for caching and rate limiting. We expanded our use cases to things like routing and request manipulation.

To help keep the catalog system afloat, we introduce many layers of caching. Some were in the application layer, and others were in Caddy, as we also discussed in our previous post. To expand on that implementation, we wanted to cache pages that relied on cookies rather than query parameters or individual headers to produce the desired response. Caddy lacked a native way to include cookie values in the cache key, so we built a custom module that copies cookie values into the query parameters. Then, let Caddy and Souin do their jobs. It would be something like the following snippet;

cache_template_builder {

prefix "KEY-{http.request.host}-{http.request.uri.path}-{http.request.header.accept-encoding}-{http.request.header.currency}-{http.request.header.accept-language}"

query_params page search sort_by order zid_language zid_currency zid_country zid_city

}

Then, that would be setting a variable that we can use with Souin.

cache {

key {

hash

template "{cache_template}"

headers Accept-Encoding Currency Accept-Language

}

mode bypass

}

The other use case for Caddy was to help with the Vitrin rollout. We needed a way to dynamically identify and route requests for Vitrin stores and non-Vitrin stores, so we built a new custom module called dynamic_host[11]. It calls the backend periodically to get the latest set of Vitrin hosts and uses that list as the matcher, like the following snippet:

@vitrin_hosts {

dynamic_host {

source http://zid-backend/hosts/vitrin

interval 10s

}

}

handle @vitrin_hosts {

route {

rate_limit_per_host

reverse_proxy vitrin

}

}

Our last Caddy use case is Hermod, the BFF layer for our new dashboard. There is a separate Caddy deployment that manages cookies and cache control for the SPA app. It’s a standard Caddy deployment with a Caddyfile full of header_up and header_down directives that manage the headers for the SPA.

More Projects to come

There will always be more projects. We know we have many sub-par areas of our systems and keep addressing them as needed arises.

The most major item on our plans for 2026 is our developer platform. We know that partner experience on partner.zid.sa and our merchant API docs are lacking. We will be working throughout the year to streamline the app creation process and ensure API uniformity and coherence.

The other major project is a multi-cloud deployment. Zid has always been an AWS house. We run the majority of our production workloads on AWS, primarily in eu-west-1. That has been going generally well, but we want more flexibility to be closer to where our customers reside, ensure compliance with less friction, and avoid disruption during major outages like DynamoDB's October 2025 outage.

We now have fully standardized on Python for any new development. ↩︎

Though MongoDB does provide ACID guarantees in a different flavour to what we are used to in relational databases. ↩︎

This is our second, independent, deployment of Caddy. Our other deployment is Zaddy. ↩︎

First contentful paint is usually affected by how fast the server can serve the page for the browser to start rendering. This is heavily affected by the backend’s architecture and performance. ↩︎

That is, Kubernetes pods, as we run everything in containers. ↩︎

Yes, the last step is rendering the templates, which is CPU-intensive, but in the grand scheme of things, this is not much time spent. ↩︎

I would argue that this was mainly due to the general attitude in the JS community. The JS community has a tendency to, whenever they dislike something in a project, go and build a new one. It leaves us with a dozen unmaintained projects that barely do the basics well. ↩︎

We tried to contribute upstream to Jinja, but seems like the maintainers were uninterested, so we published the async version as a separate package. ↩︎

Borrowing from the idea of reduction in formal methods. ↩︎

Though we have addressed that as part of our new default theme implementation – Vetro. ↩︎

We have published

dynamic_hostmodule as an open-source package. ↩︎